Let’s Make a(n) (Not) Easy $1.3 Million

In one of many moments of deliberately making myself more depressed while scrolling through Facebook, I stumbled across this post from Dave Ramsey from 2017: How to Find Extra Money and Jump-Start Your Retirement This Year.

Ramsey has helped millions of people with their personal finances, and when I am wondering about a less-familiar area (such as life insurance), his website is not a terrible place to start.

Generally speaking, you can’t go wrong with following Dave’s advice. He keeps things simple and easy to understand. That’s a good strategy when trying to reach masses of people.

However, you might run into a post like the one linked above that could actually do harm, if you’re not careful. The post includes important advice at the end about consulting a professional, but by leaving out some crucial assumptions in the numbers presented, it sets up a scenario that looks easy to reach, but is actually highly risky and unlikely to be achieved.

My issue is with this part of the post (highlighting mine):

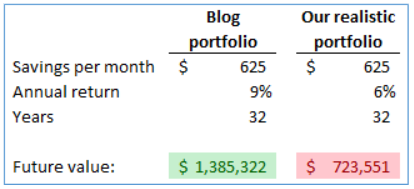

The tone of the post makes it seem relatively easy to reach at least $1.3 million in retirement savings. For a 35-year-old planning to retire at 67 (the full retirement age established by the Social Security Administration), a $625 monthly investment requires an annual return on investment of 9%.

Is 9% unrealistic? The S&P 500 has about a 10% historical average annual return, and the broader U.S. stock market has similar results (scroll to the bottom).

So it’s not necessarily a horrible rate to use, but if you were to walk into a financial advisor’s office and demand 9-10% for the next 32 years, that advisor - if he/she has your best interests in mind - might offer some words of caution.

One of the problems with 9% is the risk that would likely be required to reach that high of a rate. Early on in this 32-year period, you could absolutely take on quite a bit of stock market risk. You could even have 100% of your portfolio in stocks for a while. But as the years creep closer to age 67, your portfolio should tilt more and more away from stocks and towards an overall portfolio (with bonds/fixed income and perhaps cash) that reduces the risk of a large market downturn, which could decimate your retirement savings.

So, let’s estimate, say, a 2% decrease from an all-stock-for-all-32-years portfolio, by going with a more conservative portfolio over that time. That knocks our rate of return from 10% to 8%.

The next problem not mentioned in the Ramsey post is inflation, a killer of retirement account returns. We all know that inflation happens, but when it comes to retirement savings, many don’t understand how much it can hurt.

Thirty-two years from now, many of the same things we buy today will require more dollars to purchase. If you’ve purchased a home or are thinking of buying one, you’re probably aware of the uptick in prices over time. The loss of purchasing power over time will hurt the real returns of the portfolio. It’s going to be more expensive for day-to-day life in the future.

So, let’s knock another 2% from our annual rate of return due to inflation. Now we’re looking at a more realistic 6%. (If you want to be more conservative, you could use an even lower return.)

How is our future portfolio value estimate looking now? Much, much worse:

A 6% return compared to 9% cut the retirement savings by almost half. If $1.3 million is your minimum retirement goal, that difference is devastating. You’ll either need to work longer (12 [twelve!] more years, if we keep the $625/month at 6% assumption) or save more ($1,197/month at 6%, if 67 is the desired retirement age), neither of which are easy-to-stomach options.

Furthermore, returns are never smooth. Here is a post by Ben Carlson on sequence-of-return risk - a major factor. While exploring this risk is not the purpose of my post, note that it should not be ignored (as it is in the Ramsey post).

Estimating future portfolio values is, of course, an imprecise business. By making poor, overly aggressive assumptions, we can be mislead into thinking our goals like retirement will be easy to achieve. That’s the bad news.

The good news is that it’s not too late. Yes, those with a longer time horizon can take more risk and have an advantage over those closer to retirement. Those playing catch-up likely need to make sacrifices and might need to make some behavioral changes. But by implementing process improvements now, you can be on the road to reaching your goals.

How can you get started on or boost retirement saving? Some of the money saving tips from the Dave Ramsey link aren’t bad! At Money and the Mind, we advocate a balance between spending now and saving for the future. But if you really want or need to increase your retirement savings, redirecting current spending into retirement accounts instead is a good strategy.

Other ideas:

-Perhaps the number one personal finance strategy recommendation is to always take the employer match on 401(k), 403(b), or other employer savings plans.

-Once you’ve met the employer match, automate retirement savings. You could do this via payroll withholding, auto-directed into your 401(k), or you can set up auto contributions to a traditional or Roth IRA (the latter of which is recommended if this sounds like you). Vanguard is my top recommendation for IRAs; this link includes target retirement funds, which are perhaps the ultimate automated funds. As time passes, the funds become more conservative (i.e., a lower percentage in stocks), so large market downturns won’t decimate your account balance. Betterment is also a good place to start a retirement account; the fees are extremely low compared to an actual financial advisor (though a bit higher than Vanguard funds). The benefit is that it will customize low-fee funds for you and help you along the way, with a ton of behavioral science behind it so you don’t have to worry.

-This might seem silly or common sense to some, but if you’re contributing to a 401(k) through work or on your own in an IRA, make sure the dollars are directed into actual funds that can generate returns (especially on the IRA side; most 401(k) plans have fund defaults). For example, when opening a Vanguard IRA, your contributions might start off in a money market account (earning pennies) until you’ve set up contributions to, say, a target retirement fund mentioned above.

-If you get a raise, direct all of the increase (or as much as you can) towards retirement accounts. You’re already used to the current pay level anyway.

-One of my all-time favorite thinking frameworks comes from the book “Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending.” It goes something like this: Think of decisions from a time perspective rather than a money perspective. When we think about how we want to spend our time, instead of evaluating how to spend our money, we’re much more likely to pursue meaningful time with friends and family and/or other important pursuits, instead of approaching things from a cold, dollar and cents perspective. That doesn’t mean ignoring the money situation entirely; it might mean that you find that the ways in which you spend time are costing dollars that ultimately aren’t very meaningful to you. Using money as a tool to pursue future goals can mean spending MORE on meaningful pursuits, and ruthlessly cutting out the rest, putting the savings into retirement accounts. (A concept I learned about in “I Will Teach You to Be Rich.”)

This post doesn’t exactly fit into the category of “Personal Finance 101,” and it’s certainly not comprehensive. What’s more, not everyone is in a place where they’re considering how to save for retirement. Just making ends meet or paying off debt is a huge barrier for many. But if it’s something you want to improve or get underway, I wanted to share some ideas, and show that even a decent resource like Dave Ramsey can oversimplify. Everyone starts somewhere, and it’s okay if you’re not where you want to be. Take the smallest step. Then take the next.